|

|

|

ZEN NOTES, 2009. Summary of Contents.

Winter, 2009

- Cover: The Sixth Patriarch, From a scroll painting by Kuin (1704-1787). The Sixth Patriarch is carrying a laundry beater

on his shoulder.

- The Sutra of Perfect Awakening Forty-Ninth Lecture, by Sokei-an Sasaki, Wednesday, July 5th, 1939.

Accumulating virtuous karma does not eradicate transmigration. "The Brahmacaria do not enter Nirvana and the Abrahmacaria do not fall

into Hell." Why is this? You must not stay in avarice and thirst. You must put your mind and body into shape; follow some method by

which you can attain enlightenment!

- Bankei And His World. Zen in the Muromachi Period, (Part I, #19): The Genju-line, by Peter Haskel. The

Genju line has been called the representative sect of the Sengoku period. The Genju line formed a division of the Rinzai school. Some Genju-line

monks, like Daisetsu Sono and Hyakugai Hosho became noted rinka leaders. The principal groups participating in synthetic missan Zen during this

period were the Soto Eihei and Rinzai Daio and Genju lines. The success of the Genju line in sixteenth century Japan paralleled that of the

Myoshinji Kanzan line. Both lines stressed missan-style Zen. During the late Middle Ages, Myoshinji's attitude toward the Gozan was generally hostile, and by

contrast the Genju line's approach to the Gozan was accommodating. For many in the sorin the Genju line's secret

oral transmission must have represented a genuinely refreshing element when contrasted with the stultified Zen of their own establishments.

With the introduction of the Genju line transmission, such rudiments of Zen practice as inka, sanzen and koan study once again attained

importance in the Gozan.

- Hakuin Stories, Translated by Peter Haskel. This is the story of Chodo of Chikugo, a person of "meager endowment and

inferior spiritual potential." Hakuin said later that Chodo was one of only only two students he "went wrong with."

- Books Reviewed: The Platrform Sutra: the Zen Teaching of Hui-Neng. Red Pine, Translation and

Commentary. Reviewed by Peter Haskel. Bill Porter writes under the pen name Red Pine, and has published numerous translations from the Chinese

including poetry and Buddhist, particularly Zen, classics. He has now produced a highly readable translation of the Platform Sutra of the

Sixth Patriarch. He also provides notes and commentary in his own distinctive voice -- nontechnical, straightforward, informative but never

preachy or pretentious.

- From Our Lineage. This is taken from a recent issue of "The Middle Way", and discusses Yamaoka Tesshu, a famous

swordsman of the Meiji era and one of the founding members of the Ryomokyo Kai, a lay practice group set up by Kosen, the founding master of

the lay line of the First Zen Institute. Yamaoka Tesshu's calligraphy was recently on display at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London,

November 2008. This article discusses his sword practice and his Zen practice.

- Illustration from "Life-Giving Sword", by the famous swordsman Yagyu Munenori.

- Illustration: Tiger, by Susan Morningstar.

Spring, 2009

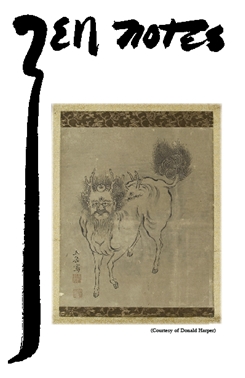

- Cover: Baize. The baize is a predator which eats bad dreams. (Cover art courtesy of Donald Harper).

- The Sutra of Perfect Awakening, Fiftieth Lecture, by Sokei-an Sasaki, (July 12, 1939). By right endeavor, everyone

can attain Perfect Awakening. To do so, they must follow the Vinaya, Sutras and Abhidharma -- morality, practice and philosophy. In Buddhism, we

do not use the word "God", we use the word "Reality." There are five types of men: agotaras, sravakas, pratykabuddhas, bodshisattvas and buddhas

-- these are the five types of religious mind.

- Three-Hundred-Mile-Tiger, Sokei-an's commentary on The Record of Lin Chi. Discourse XI, Lecture 5. This is a commentary

on the famous quote from Lin Chi: "Even if Manjushri or Samantabhadra were to appear before me, manifesting themselves in my presence to ask me

about the Dharma, the moment they open their mouths I would understand [the falseness of their attainment]." Samantabhadra and Manjushri are

Bodhisattvas -- the personified doctrines of fundamental wisdom. Manjushri is absolute consciousness. Samantabhadra is the consciousness in

each existence.

- Book Review: Zen Baggage: A Pilgrimage to China. by Bill Porter (Red Pine), Reviewed by Michelle Bromley, and

reprinted with permission from the Middle Way, Vol 84 #4. Bill Porter takes us through present-day China, from Beijing to Hong Kong, visiting sites

associated with the six patriarchs of Zen. Bill Porter spent 22 years living in East Asia, and in this book retraces steps he has taken earlier.

One of the main themes of this book is the revival of Buddhism in China today. After the fall of the Qing dynasty in 1912, years of war, the

Great Leap Forward and the Cultural Revolution, Buddhism is making an amazing and extremely strong come-back.

- Bankei and His World, by Peter Haskel. Zen in the Muromachi Period (Part I, #20). Continued from

Winter '09 Zen Notes. Missan Zen is a difficult subject. Despite its pivotal role in the Zen schools of the late Middle Ages, we lack precise

knowledge of much of its history and workings. Compared with the original Zen of the early founders such as Dogen and Daito, or with the

teachings of later masters such as Bankei and Hakuin, missan Zen appears curiously formalized and degenerate. Missan Zen managed to preserve,

albeit in a distorted form, koan study, sanzen and inka. It also embodied a uniquely Japanese adaptation of Buddhism and specifically of Zen.

This article includes an historical discussion of Sung-dynasty Zen in China, the rise of the koan system, and the appearance of koans and capping

phrases in the Blue Cliff Record, first published in 1128. Zen study in medieval Japan meant primarily koan study, and the selection of

appropriate capping phrases was considered to be of great importance.

Summer, 2009

- Cover: Monk with Staff, Drawing by Seiko Susan Morningstar.

- The Sutra of Perfect Awakening, Fifty First Lecture, by Sokei-an Sasaki (September 20, 1939). There are two obstacles

preventing the attainment of enlightenment. One comes from circumstances, and the other from some idea or notion that is planted in your mind.

"Awakening" is a better term than "enlightenment." It is like awakening from a dream. Confucius said that when he was twenty he awoke to learning, at

thirty he awoke to his aim, at forty to his decision, at fifty to his limitations, at sixty to the affirmation of everything, and at seventy to true

freedom. All human beings must pass through many periods of awakening, but in Buddhism, there is a particular type of awakening called "satori."

- Three-Hundred-Mile-Tiger, Sokei-an's commentary on The Record of Lin Chi. Discourse XI, Lecture 6. When Lin-chi seats

himself he is different from other people, he has nothing in his mind, no mind-stuff. In Japan you will see pagodas that signify the enlightenment

stages of tathagata, manu and deva. Lin-chi sees through the three stages of enlightenment: enlightened body, soul and substance. The prime or

essential ground of wisdom is dharmakaya, the three dharmakayas: the dharmakaya of tathagata, of manu and of deva. Lin-chi does not stay in any of

these, the root, trunk or branches. He penetrates all.

- Fearless Mountain, A film by Tony Anthony and Andrew Anthony. Reviewed by Ian R. Chandler. Abhayagiri means

"Fearless Mountain" in Pali, and Abhayagiri monastery is located in Redwood Valley California. The calm, intelligent monks in Fearless

Mountain are unapologetically Buddhists in the Theravadin tradition, with everything that implies: celibacy, vegetarianism and long hours

of meditation and manual labor. This hour-long film is the distillation of 72 hours of filming, along with professional-quality editing

and cinematography.

- Twenty-Five Koans (Ninth Koan) This is Sokei-an's commentary on the dialogue: "One day Joshu went to

see the stone-bridge with the head monk. Joshu questioned him, 'Who made this stone bridge?' The head monk answered, 'Li-yuan made it.' Joshu

said, 'When he made it, where did he first put his hand?" In his commentary, Sokei-an's says that Joshu affirms nothing; he accepts everything.

He does not deny even the cockroach in the kitchen. Included is an additional dialogue between Joshu and Nansen. "Joshu" is also the name of

a town in northern China which was home to the monk Joshu.

- Bankei and His World, by Peter Haskel. Zen in the Muromachi Period (Part I, #21) Missan Zen.

There was a considerable difference between Daito's Zen instruction and that of the missan teachers of the late Medieval rinka. Ritualized

missan transmission dominated late Muromachi Zen. Based on secrecy and exclusiveness, Missan Zen's origins can probably be traced to the Kamakura

period. The Chinese Master Wu-hsueh Tsu-yuan, founder of Engakuji, commented caustically on the Japanese priests: "There is a class of Zen

priest who, having failed to grasp his own original nature, merely turns to a notebook, memorizes[certain items], and then comes forward to present

his answer [in sanzen], even giving detailed instruction [in this] to others and babbling the wildest nonsense." In 1303 Muso Soseki experienced

a profound realization and then threw into the temple kitchen's fire the notebooks in which he had recorded his sanzen experiences with the various

teachers under whom he had studied.

- Butterflies, drawing by Susan Morningstar.

Fall, 2009

- Cover: Red Pine (Bill Porter), Photo by Julie Anand.

- The Sutra of Perfect Awakening, Fifty Second Lecture, by Sokei-an Sasaki, (September 27, 1939). Every sentient being has

the capacity to awaken if he meets a good teacher and practices the true method. As Confucius said, "A true word is always repulsive to erroneous minds!"

The manifestation of Dharmakaya in the human mind is like a wave, a storm, like lightning. Teaching must be given with great care.

- Dancing With Words: Red Pine's Path Into The Heart of Buddhism., by Roy Hamric. This is an updated version of an article

that originally appeared in The Kyoto Journal. Who is this Red Pine? He lives in the mountains overlooking Taipei in a small farm community called

Bamboo Lake. He is a prolific translator of Chinese Zen writings, and his translations include The Mountain Poems of Stonehouse, The Poems of Cold

Mountain, The Zen Teachings of Bodhidharma, Guide to Capturing a Plum Blossom and Road to Heaven: Encounters with Chinese Hermits and

a stunning translation of The Diamond Sutra. His translations seem inspired, and he loves the authors whose works he has translated. He lives frugally, since royalties

are his only source of income. He enrolled at Columbia grad school, where he received a fellowship to study Chinese, and spent weekends meditating with

a Buddhist Hua-Yen monk, Shou-yeh. Eventually, he moved to Taiwan, and studied with Wu-Ming, who had been Chiang Kai-shek's personal master. This is a

farily involved account of Red Pine's life story, and it makes interesting reading.

- Bankei and His World, by Peter Haskel. Zen in the Muromachi Period (Part I, #22) Missan Zen.

It is difficult to assess the extent to which the missan transmission in Ikkyu's period altered traditional Zen practice in the great rinka temples such

as Daitokuji, Myoshinji, Sojiji and Eiheiji. Although the more familiar, dynamic character of Zen seems to have persisted, there remains no doubt that

Myoshinji, like Daitokuji, succumbed to the influence of missan Zen in the late Muromachi period. Suzuki Daisetsu's pioneering research uncovered

missancho from all four of the principal Myoshinji lines, which probably embody transmissions evolved during late medieval times. The latter half of

the sixteenth century was a particularly active period for missan Zen. This article includes a table of Daitokuji teachers and the dates of their

missancho, along with a ringing denunciation of the entire system of missan Zen by the Obaku sect teacher Choon Dokai (1628-1695) -- paralleling Ikkyu's

earlier denunciation of missan Zen in his "Jikaishu."

Table of Contents

|

|